To this day, Arsene Wenger remains the only Premier League manager to win the title without losing a single game all season.

His story at the helm of Arsenal’s ‘invincibles’ season has been repeated time and time again. However, his time before arriving in England is a tale told far less often.

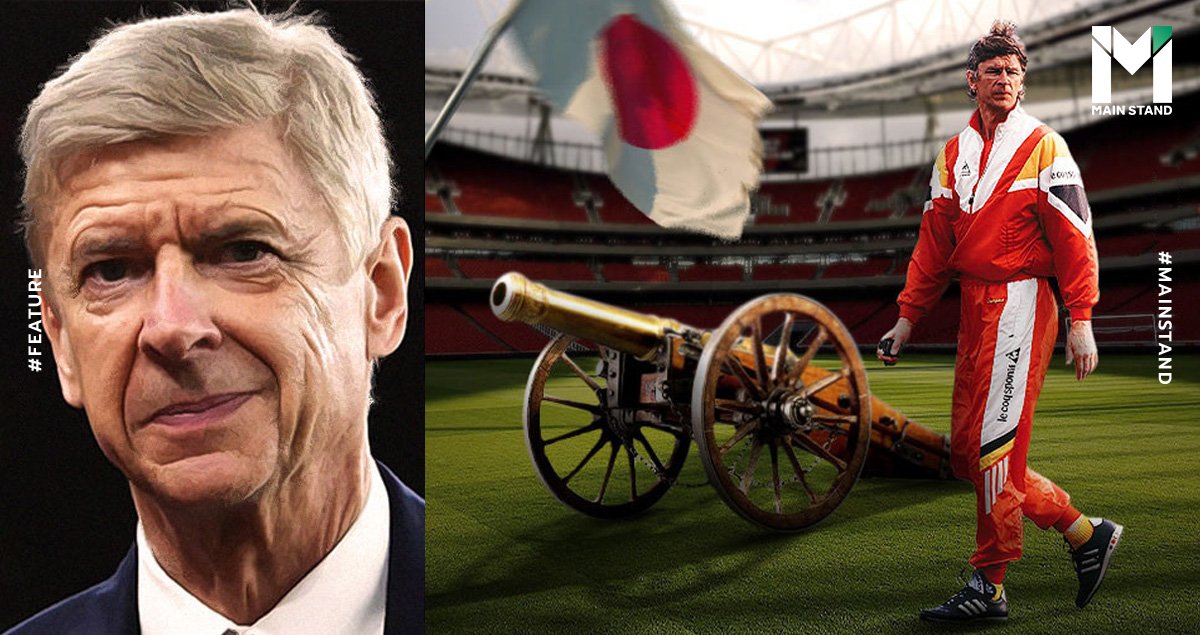

This is a story about Wenger’s 18-month stay in Nagoya, Japan. It is about his struggle working in a country with an unfamiliar culture and language, leading to an unexpected turning point in his illustrious career.

Follow along with Main Stand to find out about Arsene Wenger’s time in charge of Nagoya Grampus.

The 100-year project

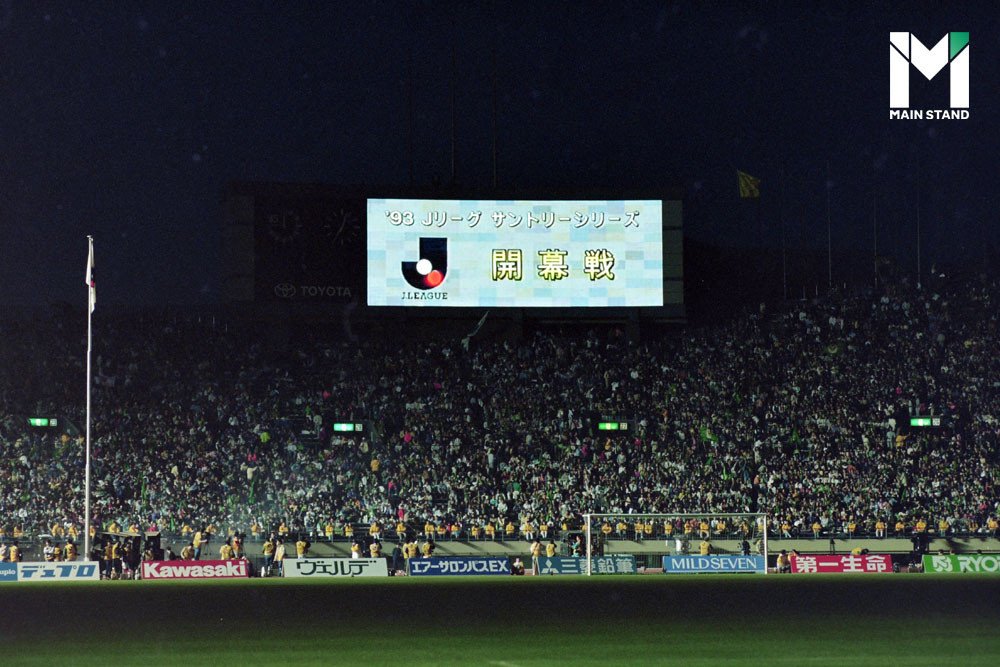

The Japanese football league can trace its roots back to the 1960s when it was comprised mostly of teams run by major corporations and conglomerates. Starting in 1993, the league experienced a major takeoff, as clubs began to be associated more closely with local areas and were able to cultivate ever-growing fanbases. That season, J.League matches saw an average of 18,000 spectators per match.

With attendances on the rise, clubs began to enjoy increased revenues and were able to invest in improving their teams. As a result, recruiting both foreign coaches and players became more common.

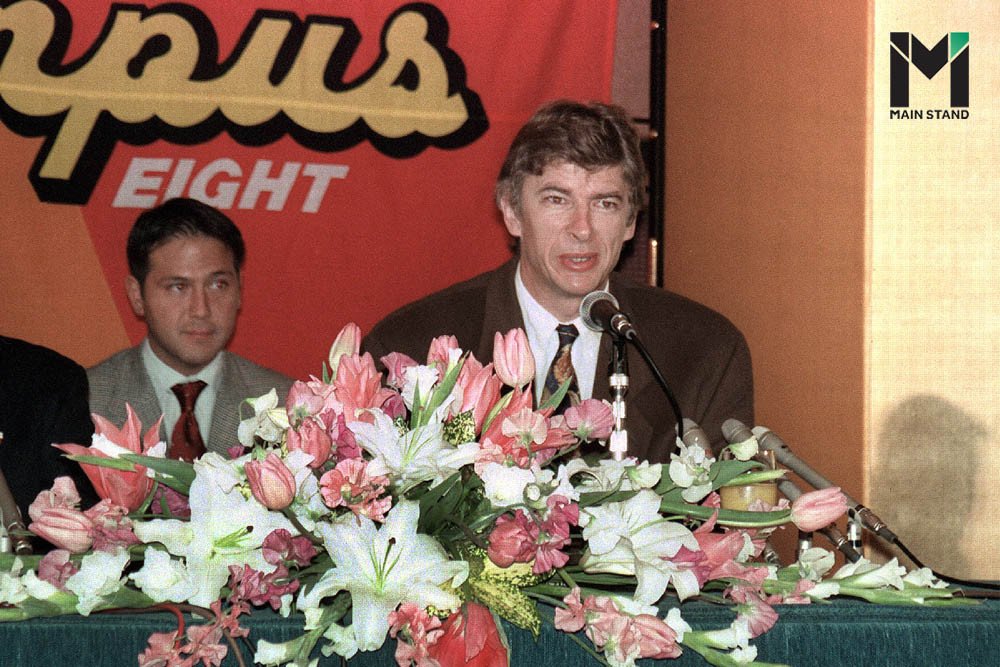

In 1995, Nagoya Grampus, which was in need of a European coach to improve their performance, was interested in hiring a French coach named Arsene Wenger. Wenger had previously coached two teams in the French Ligue 1, Nancy and Monaco, taking charge of a total of 350 league matches. During his time in Monaco, Wenger won the league during the 1987-88 season, as well as the domestic cup in 1991.

His appointment was seen as unusual at the time, as successful managers in the French league would normally be on the radar of top clubs in Europe. Why did Wenger accept the offer from Nagoya Grampus?

By 1994, Wenger had been coaching Monaco for six years and was experiencing a major slump in form. When rumors about his dismissal began to spread, Wenger admitted to being so stressed that he allowed his determination and performance on the training pitch to drop.

“It was the most difficult period of my life,” Wenger reflected in 2013. “When you’re in a job like mine, you worry about every detail. But then to go to work and know that it is all useless, it is a disaster.”

Wenger began to question the very fundamentals of his work and simply wanted the opportunity to enjoy his life and career again.

That opportunity would eventually come in the form of his meeting with Shoichiro Toyoda, the chairman of car manufacturer Toyota, which owned Nagoya Grampus. Toyoda told Wenger that the club wanted him because of their ambition to be the biggest team not just in Japan, but the entire world, within 100 years.

This idea sounds so fanciful, it may as well be the plot of a Japanese Manga. Wenger was aware of how unlikely it was that a Japanese club would ever be the greatest in the world. When compared to Europe, which had been professional for many years, Japanese football was still in its infancy.

However, the offer reached Wenger in a time of major upheaval, when he was confused about his approach to management or even his suitability for the profession altogether. Nagoya’s proposal was a breath of fresh air, a change of perspective, and something he couldn’t afford to turn down.

“That negates the pressure of immediacy in a fabulous way,” Wenger would later explain. “What does it matter if you lose, if your target is a century away? I also found that idea extremely generous. Only being a conveyor belt in history, as a part of a movement that is much larger than you are. Being part of something that is beyond you. Unfortunately, we live too often with the idea that the world is going to stop after us. That is not humanity.”

Just another foreigner

Back in 1994, Nagoya Grampus was far from being the strongest team in Japan, let alone the world. They finished the first leg of the season in 8th place, before plummeting to the bottom of the standings for the second half of the campaign.

Wenger first arrived in Japan in late 1994, but wouldn’t actually begin coaching the team until March 1995. He spent his first few months in the Far East learning about the culture and preparing his coaching staff. He contacted a Bosnian coach, Boro Primorac, to be his assistant, and became familiar with the personnel already at the club.

What was most crucial for Wenger was to find a reliable interpreter. Fortunately, he met Go Murakami, who was able to fluently communicate with Wenger in English.

“I heard he came from Monaco and I didn’t know about him, but everyone said he was a good manager from France,” Go explained. “I spent one-and-a-half years at Grampus and I was always with him, he was a hard worker.”

A key message Go had to translate for Wenger was that major changes were afoot at the club. This included diets, mentality, and training methods. He demanded that everyone believe in and comply with his suggestions.

“At the beginning, we had a seven or eight-game losing streak, it was difficult at first,” Go recounted. “He [Wenger] knew everything about nutrition and the mental side, how to control the players. He tried to adapt to the Japanese style, we were just at the beginning in terms of football.”

Japan has a long history of nationalism and suspicion of foreign influence, meaning Wenger needed a way to break the ice and have the players buy into his new methods.

“There was a wall between me and the Grampus players,” Wenger recalled. “The know-how I had developed in Europe was of no use with this wall.”

“No one trusted Wenger at first. They all said ‘here comes another foreigner’,” said defender Tetsuo Nakanishi to FourFourTwo.

Wenger’s resolution was to take a hands-on approach. He coached the team himself in every session, teaching the players to possess, intercept, and pass the ball. Since such skills are the fundamentals of football, many complained that they felt as though were back to school. Although Wenger was aware of the players’ criticism, he plowed forward regardless, reminding them that the basics are first and foremost in football.

However, there was little incentive for the team to improve. With no threat of relegation (due to the league’s structure at the time), there was nothing motivating the squad, which had been drained by frequent losses. Despite his extensive work, there was little progress in the team’s ability to control possession, meaning he was unable to impart his vision for the team.

One day, a way out suddenly crossed his mind. The solution was a lot simpler than he expected.

Unite and Change

Wenger soon realized that the difficulty he was facing was not because his players were headstrong or ignored what they were taught.

Instead, the problem was that they believed in what they were taught too much, and followed instructions like robots, as opposed to playing football in an imaginative manner. They thought that improvising would be viewed as disrespectful to their new coach. As a result, Nagoya’s football was dull, ineffective, and predictable.

“They wanted specific instructions from me, but the player with the ball should be in charge of the game. I had to teach them to think for themselves,” Wenger recalled.

Now that he understood the issue, Wenger was finally able to address it. He encouraged his players to be bold, to dare to dribble and score. They were not bound by his vision or principles, but rather they were able to play as they saw fit in order to score.

This caught the attention of Dragan Stojković, a member of the Yugoslavia national squad, who spent the latter days of his career with Nagoya. Earlier, Stojković was not a disciplined player and found himself tired of the monotony of training. But Wenger’s arrival rejuvenated him, and soon he was back to giving his all in training and competitions.

“Arsene Wenger changed everything at the club and he showed the players that they could enjoy playing football, enjoy training,” said Stojkovic. “It wasn’t just a job, but that they could express themselves. It took time but the players started to respond.”

Wenger fell in love with the game once again in Japan, and his trademark attention to detail was back in full force. He arranged oil-free diets for the players with less acidic fruit and vegetables. He brought the team together by saying “Arigato gozaimas” (thank you very much) every time the players follow what he told them to do.

Not only was he strict with his players, but also with himself. Boro, Wenger’s assistant, recalled that Wenger had little sleep prior to matches because he had to watch videos of the opponents’ performance for analysis, and he finished doing so at around 3 a.m. Sometimes Boro would finish work, but Wenger was still keeping his head down, preparing ways to brief his players for the next game.

Wenger’s effort soon reaped rewards for Nagoya, who were fourth by the end of the season’s first leg. Buoyed by this achievement, they went on to finish second in the league and even managed to bring home the Emperor’s Cup, Nagoya’s first trophy in the professional era.

“Wenger brought a modern managing style to Nagoya,” explained Japanese journalist Shintaro Kano from Kyodo News. “He meticulously controlled every aspect of the club, the way he did at Arsenal for more than two decades. Wenger’s style fits well with the mentality of Japanese players, who are accustomed to such discipline.”

Lessons from Japan

Wenger’s 18-month tenure in Nagoya flew by and ended with both the Emperor’s Cup and Japanese Supercup added to the club’s trophy cabinet. More importantly, though, it restored his joy in football management.

“Japan taught me to learn about flexibility, determination, and letting go of things,” Wenger concluded. “What I learned can be applied to all things in life and all levels of football. I returned to Europe as a new version of myself; I have become assertive and calm.”

Similarly, Wenger’s time in Nagoya Grampus was a major turning point in the history of the club. He used the power he was given to develop the organization and professionalize the club in a way that was previously unseen in Japanese football. His time at the club remains legendary to this day.

We have no idea of knowing if Nagoya Grampus will achieve its goal of being the world’s greatest football club in 100 years, but we are pretty confident that the story of Arsene Wenger will still remain a major source of pride for the club throughout all that time.

Sources:

https://thesefootballtimes.co/2018/05/17/how-18-months-in-japan-set-arsene-wenger-up-for-glory-at-the-top/

https://www.goal.com/en/news/a-philosopher-in-football-arsene-wengers-former-translator/1babfd5oot0k21snzbpmjoqscd

https://www.fourfourtwo.com/features/wenger-nagoya-grampus-eight-how-arsene-rediscovered-his-greatest-love-japan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ars%C3%A8ne_Wenger

https://the18.com/soccer-news/when-arsene-wenger-was-emperor-japanese-football