Without a peaceful land to dwell in, just having wealth cannot earn you true happiness.

Here's the story of a football player who went beyond managing goals. With an overwhelming love for his homeland, he couldn't leave the ongoing national conflicts behind. So instead of living a successful life, he chose to play a pivotal part in terminating such animosities.

Main Stand will share a story about how Didier Drogba scored more than just goals.

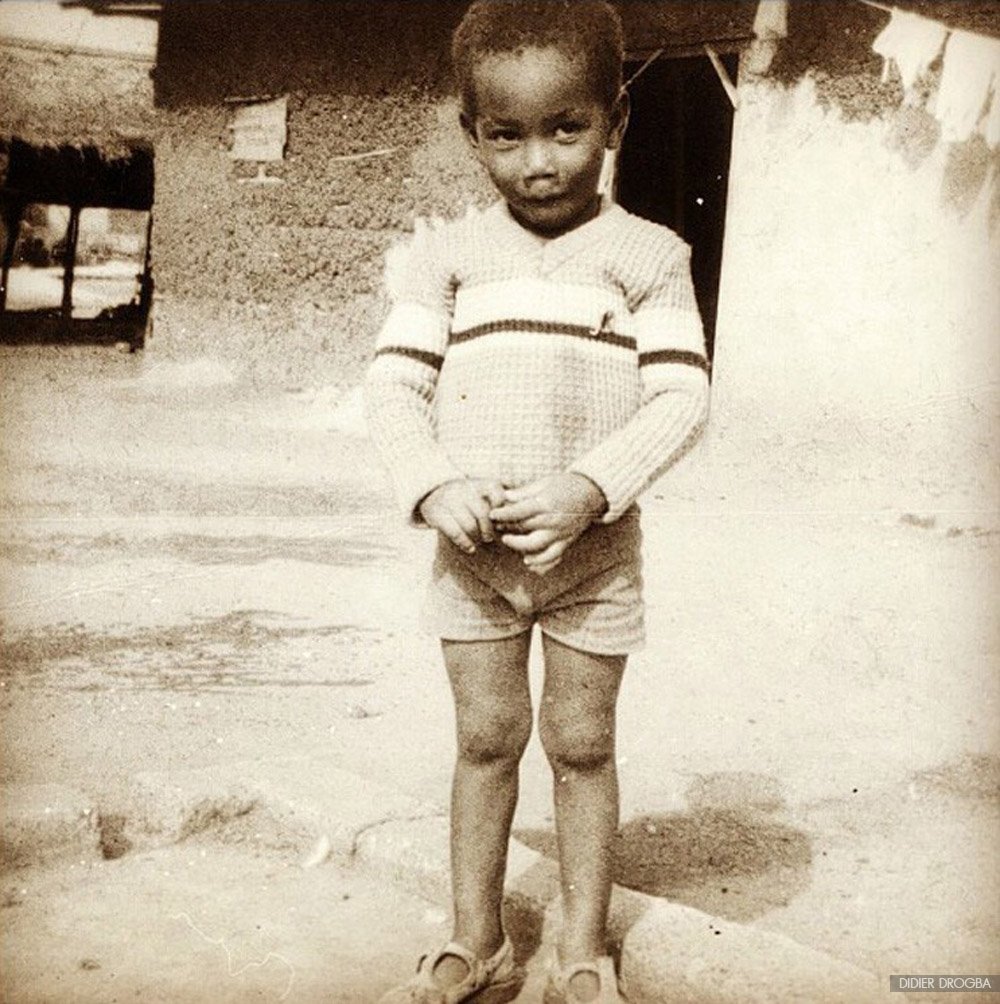

Life of a young Didier

In 1978, in Abidjan, the economic center of Côte d'Ivoire, amidst financial crises, two local bankers, Albert and Clotilde Drogba, gave birth to a boy named Didier Yves Drogba Tébily.

Clotilde nicknamed him "Tito" after Josip Broz Tito, a Yugoslav communist revolutionary, which means "giant" in Italian and Spanish. Regardless of its definition, both of them earned a modest income, so all they could do was imagine their son was nourished with plenty of food, contrary to the unfortunate fact that Didier was malnourished.

Mr. and Mrs. Drogba hoped to get their five-year-old son out of malnutrition, so they sent him to France. He was an African boy on a plane, flying to a new continent to experience a new life, with a tag hanging on his neck that read, "DIDIER DROGBA TO MEET MICHEL GOBA IN PARIS."

Michel Goba, Clotilde's elder brother, moved to France to play professional football. When he adopted Didier, he was only a 22-year-old star player for Stade Brestois 29, a lower league in France. Goba was not a well-paid player.

Just a side track, this was the time when Africans migrated to France to make a living by playing football.

When five-year-old Didier arrived in France, he had to live in a tiny room with his uncle, who was responsible for caring for him and taking him to training sessions every day.

"I remember my early life in France. I cried every day. Not because I was in France – I could have been anywhere – but because I was so far away from my parents. I missed them so much," Drogba recalled his childhood.

Three years later, his low-profile footballer uncle gave up looking after his nephew. So an eight-year-old Drogba returned to Ivory Coast. No matter what their parents or uncle thought, he was glad he was home again, as it was what he had dreamed of for three years. Côte d'Ivoire was his home.

But his dream was a far cry from reality. Three years after he returned to his parents, many African countries faced economic downturns, so he was under his uncle's supervision again. However, it was a long time before he could return to his home country. Drogba had to receive an education or play football to live a life, and he could return to his parents.

Everything went seamlessly. Drogba had played for a youth team until he managed to play for a famous team such as Le Mans and became part of the Ivory Coast national football squad in 2002.

Finally, his long-awaited dream came true. When he was 24, he successfully returned to his home nation in front of Ivorian football fans after he had been away for 10 years. Unlike many African countries, he last pictured Abidjan was rife with smiles, with no guns and bombs. But what happened in 2002 shattered his heart.

From a peaceful land to a battlefield

In 2002, Didier Drogba represented the Ivory Coast team. He and his fellow Ivorian players returned to Côte d'Ivoire to compete in the 2004 African Nations Cup Qualifiers against South Africa at the Stade Félix-Houphouët-Boigny, Abidjan, in early September.

Drogba had been aware of political unrest in his home nation, but he never thought there would be so much tension that army forces and tanks were ubiquitous on the streets. And it stemmed from political discords.

In 1999, a coup d'état emerged in Côte d'Ivoire, becoming a military-led country. Although Laurent Gbagbo won a presidential election in 2000, political riots persisted. The government-led side fought against the opposition led by Alassane Dramane Ouattara.

Through the United Nations (UN), French troops and the UN attempted to calm the civil war, but it was unsuccessful.

The combatants of both sides opened fire anywhere, whether on roads, in schools, or in hospitals, resulting in several casualties. There was no end in sight to this violence.

"I left Cote d'Ivoire with a certain image: It was beautiful, its streets were lovely, greenery everywhere and people were happy. And when I came back a few years later, I saw a real change. That's when I started asking myself questions," Drogba said.

Drogba mentioned what happened in 2002 when people were displaced as they had no choice. Many small villages were seized and turned into military bases.

The rifts often arose in Abidjan, Drogba's hometown, so the area lacked necessities, which left him crestfallen. Worse still, no sooner did the military side grow into full-scale rebellion than the match against South Africa had ended.

Drogba is scoring essential goals off pitch

The perpetual rifts were getting even worse. There had constantly been fighting and killing since September 2002. Even so, Didier Drogba never gave up on helping his compatriots, even after he knew that his homeland was in bloody turbulence. But the due time was yet to come. Unfortunately, he was not famous or powerful enough to cause political changes.

Didier Drogba was getting more skilled as a professional football player. So, after playing for a small side like Le Mans, he moved to Guingamps and Marseille. Eventually, he moved to Chelsea under José Mourinho in 2004 for £24m.

The more recognizable he was, the louder his voice was. But, sure enough, as a national icon of the Ivory Coast, he was more reliable than any politician.

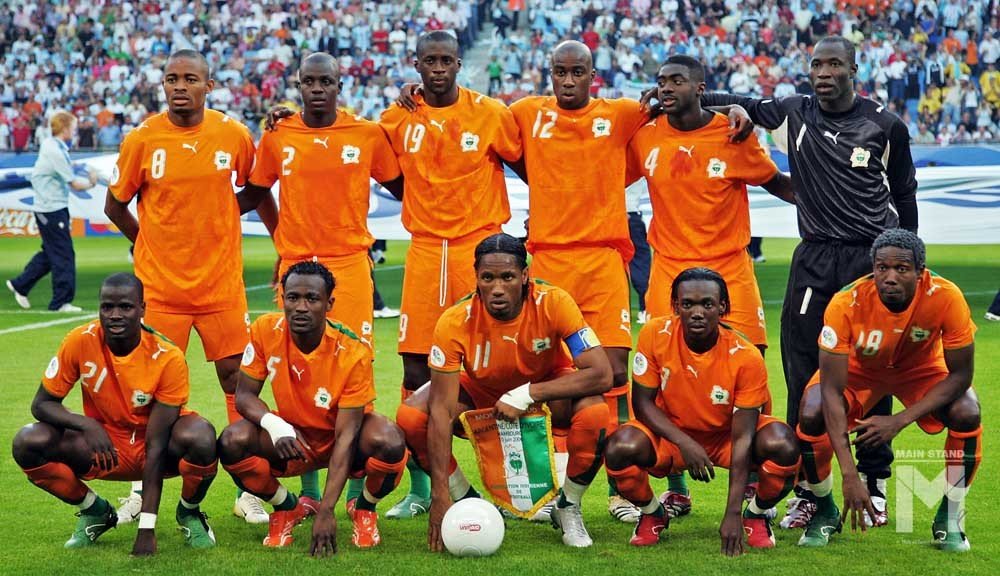

Everything happened at the right time. Football in Ivory Coast made a massive leap in the 2000s. The JMG Academy gave birth to myriads of up-and-comers, despite its failure in Egypt, Thailand and Vietnam. All new-blood players were highly motivated to escape poverty and their fragmented homeland.

They made more significant strides to become the cream of footballers and make their way to play football in Europe. As a result, tons of White Elephants players in Yaya Touré, Kolo Touré, Emmanuel Eboué and Salomon Kalou emerged.

They significantly inspired young generations to use football to change military factions' minds. It was perfect timing. The 2006 World Cup was around the corner, and Côte d'Ivoire was a footballing country. However, it never made it to the finals. Therefore, Drogba's statement that it was their first World Cup sounded profoundly motivating.

"I knew that we could bring a lot of people together, more than politicians," the striker said in 2011.

"The country is divided because of politicians; we are playing football, running behind a ball, and we managed to bring people together," he added.

Although no one thought it would be possible, what he said had gradually been actualized.

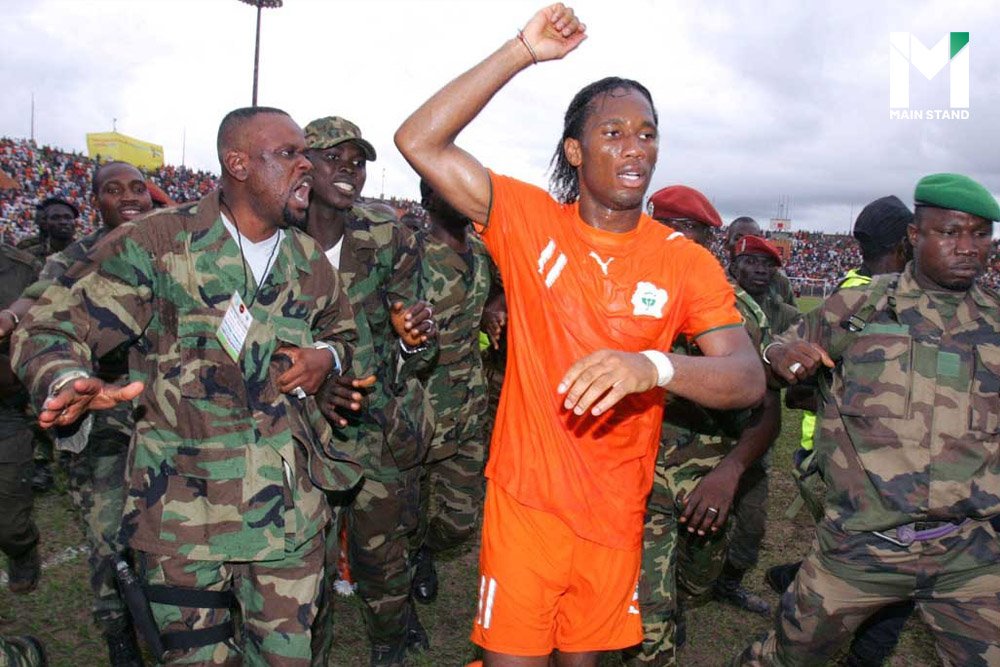

On October 8, 2005, Côte d'Ivoire triumphed over Sudan, with a 3-1 win, in the last game of the qualifiers, steering themselves to the first World Cup in history. Some might think this was the pinnacle of Ivorian football. However, it was only the beginning.

After the game ended, correspondents were ushered into the mixed zone to interview the Ivorian national team about their big day. However, none of them appeared except defender Cyrille Domoraud. He called the media to the changing room.

They expected to write a headline about Ivorian football at the international level. But things were not as expected. All the players agreed to hand the microphone to Drogba, and the most heartfelt speech began.

"Men and women of the Ivory Coast," he said down the lens, his face stern and sincere.

"From the north, south, center and west, we proved today that all Ivorians can coexist and play together with a shared objective: to qualify for the World Cup. We promised you that the celebration would unite the people.

"Today, we beg you, please – on our knees – forgive. Forgive, forgive," he continued his influential speech.

"The one country in Africa with so many riches must not descend into war like this. Please, lay down all weapons. Hold elections, organize elections. Then, all will be better."

This was big. There was no such celebration as drinking wine or champagne. Instead, it was a message to all Ivorians, regardless of their political ideologies.

Once the sentence ended, the Ivorian players cracked a smile, sang the national anthem in a deafening way in the changing room, and finished with a particular song, "We want to have fun, so stop firing your guns."

Although he was neither a prime minister or president, Drogba's voice was heard nationwide. Ending the ethnic tensions was not easy, but it was possible. He was like a representative for people to work toward reconciling the conflicts between the two sides.

"I felt then that the Ivory Coast was born again," Drogba said, sensing a massive change after making a plea with both sides' leaders.

Unfortunately, it took up to three years to end this and gain back liberty.

What happened in Bouaké

He was at the pinnacle of his career when he led Chelsea to the Champions League title in 2012. However, the zenith of Ivorians had happened before that.

The 2008 African Nations Cup was getting closer, and Drogba realized it was time what he had done all along yielded a result.

It became more apparent in the qualifiers against Madagascar on June 3, 2007. It was only their third match, but it was the last game he would play in their homeland.

The Ivory Coast national football team would compete in the government's base in Abidjan. However, Drogba requested the Confederation of African Football to select a new venue in Bouaké.

Bouaké is the second largest city 300 km farther in the north. This was a former insurgents' stronghold and was the first time in a decade that the armed struggle was the most likely to emerge as the two rivals would encounter each other.

To ease the matter, Drogba pleaded with Gbagbo to grace the match and negotiated with opposition Alassane Ouattara to ensure safety.

On the match day at an outdated stadium, the leaders of both sides met for the first time at the Stade Bouaké. All 25,000 spectators eyed how the two, the causes of bloody wars and hostilities, held their hands for fear that there would be turmoil. But Drogba looked at what was happening proudly and was confident that his endeavor would eventually pay off.

"Seeing both leaders side by side for the national anthems was very special," he told the Telegraph, the only English media that headed to Abidjan to interview Didier Drogba.

When asked who backed him in doing so, Drogba smiled and replied, "All Africans backed me. But, above all, I am one of them."

The stadium was packed with cheering voices no sooner than the national anthem had faded. This was a testament to the end of the civil war. From now on, all the spectators would be rewarded with what the Ivorian footballers promised, "we promised you that the celebration would unite the people."

Ivory Coast beat Madagascar 5-0, and fans flocked to the pitch with jubilation. Unfortunately, the rampage went beyond a thousand security guards' control. However, this was a rampage of jubilation.

It was like a movie: ending happily after a long misery. But, then, a vast bonfire blazed again. However, it was not a bonfire of destruction; it marked the reunification of the two opposed territories.

They joined hands, throwing firearms into the fire as if the fire blessed all the unification.

And finally, in December, all the wars had officially ended. Both the governments and rebel forces disarmed soldiers on the borders. Ivory Coast was one.

Drogba, whose hometown is Abidjan, said he could live without money and dedicate all his assets to spending the rest of his life in his home country.

Ivory Coast is the only thing he devoted his life to unconditionally.

As a result, many hospitals, schools, and foundations arose in the name of Drogba, funded by the big man himself.

To him, money didn't play a crucial role in the country's development; it was education that could benefit the nation.

"The money came after my education after I became a man," he said. "I have won many trophies in my time, but nothing will ever top helping win the battle for peace in my country. I am so proud because today, in the Ivory Coast, we do not need a piece of silverware to celebrate.

"There are no words to express how I feel right now. This is love," he concluded.

Sources:

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/football/international/2318500/Didier-Drogba-brings-peace-to-the-Ivory-Coast.html

https://edition.cnn.com/2017/11/11/football/ivory-coast-didier-drogba-stops-civil-war-copa/index.html

https://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/footballrebels/2013/03/201336105035488821.html

https://www.stmuhistorymedia.org/the-power-of-a-ball-how-soccer-star-didier-drogba-ended-the-cote-divoire-civil-war/

https://thesefootballtimes.co/2015/03/17/didier-drogba-a-man-of-peace/

https://www.peaceinsight.org/conflicts/ivory-coast/

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13287585

https://www.bbc.co.uk/bbcthree/article/8bd562a5-4f9f-4221-903d-b3e80c162e5d

https://www.bloggang.com/viewdiary.php?id=shalaya&group=4

https://culanth.org/fieldsights/187-a-history-of-crisis-in-cote-d-ivoire