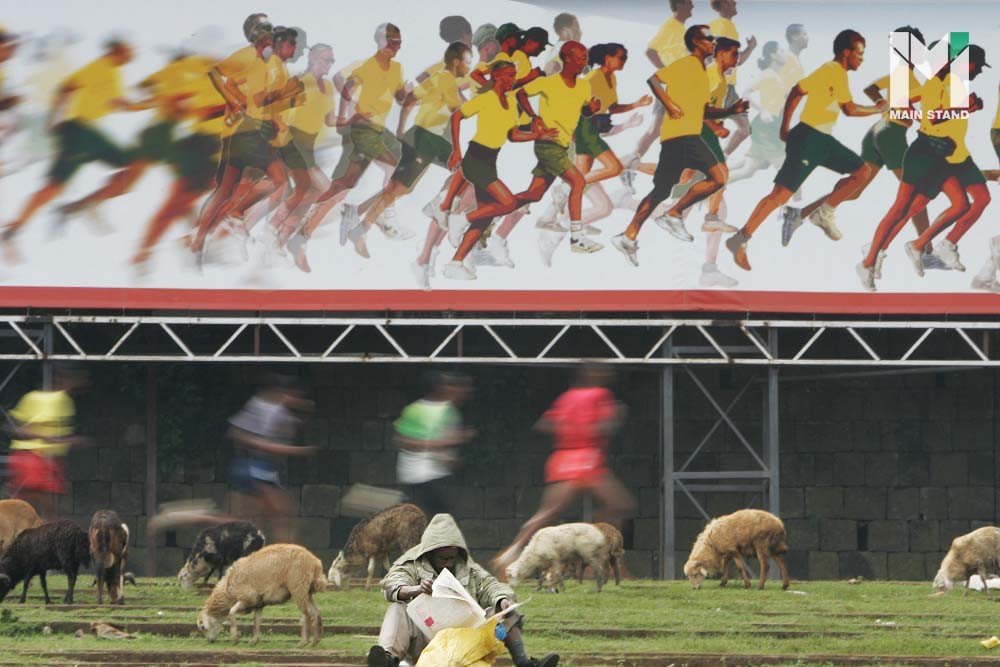

Over both long and short distances, Asian runners don’t tend to see much success on the international stage.

Curiously, the region has produced a number of exciting young talents in the sport. However, as they get older, they struggle to make an impact at the highest level when facing off against the world’s best athletes.

What explains this phenomenon? Why does the gap in skill grow with age? Come and find out with us at Main Stand.

The success of youth runners in Asia

Puripol Boonson is a fan favorite sprinter, nicknamed “Tep Bill'' (Tep means godly in Thai), who holds the record for 200m dash in Asia at 20.19 seconds. His accomplishments are only the start of his international competition career, as he is still only 16 years old.

Even at his young age, he had achieved 4th place in the 100m dash in the 2022 IAAF World Championships in Athletics, missing out on a medal by milliseconds. His exploits so far have led fans to think that Thailand may soon have an Olympic medal-winning sprinter.

Puripol isn’t the first sprinter from the region to reach these heights. Previously, Indonesian runner Lalu Muhammad Zohri took home the gold medal in the 100m dash at the 2018 IAAF World Championships.

Asia's track and field scene has seen great strides in the past few years. China has risen to be one of the top contenders on the continent, with new athletes being in contention for medals in international competitions. Prior to this, China had never qualified for the final round of the 100m dash in the Olympics, but the last 20 years have seen them make huge advancements in sports science and techniques, giving rise to many top-class sprinters.

In their youth, these Asian athletes can hold their own against international competition with differences of only milliseconds. However, when it comes to the Olympics or IAAF World Championships, why do Asian athletes always fall off?

Genetics

The most straightforward explanation is that sprinting is a sport that purely utilizes physical prowess. Equipment has a minimal effect on the athlete’s performance. A strong body, long limbs, and muscles built for running are some of the reasons Asian genetics aren’t suited for track and field over both short and long distances. This is not just speculation, as there is solid evidence regarding the matter.

In terms of sprinting, there has been researched on successful Jamaican runners by Earl Morrison, a professor from Kingston University. He found that 70% of Jamaican athletes have the compound Actinen A in their muscles. The chemical compound is responsible for many cell functions such as cohesive mechanics of the strength and is also referred to as the “speed gene” because of its role in generating acceleration.

The research also found that Jamaican athletes had up to 30% more Actinen A than Australian athletes who assisted with the study.

Other than the speed gene, it is also a matter of body proportions. Asians are at a disadvantage to Jamaican or African sprinters, who have longer legs. David Epstein, the author of The Sports Gene, discussed his theory that people of African descent have the highest height ceiling and longer limbs than people of other genetic backgrounds.

“For any given sitting height - that is the height of one's head when one is sitting in a chair - Africans or African-Americans have longer legs than Europeans. For a sitting height of two feet, an African American boy will tend to have legs that are 2.4 inches longer than a European boy's. Legs comprise a greater proportion of the body in an individual of recent African origin. And this holds for elite athletes,” Epstein writes in The Sports Gene.

The impact of this difference in body proportions doesn’t just make an impact on the track and field scene. For example, the tallest Asian athlete in the NBA, Yao Ming stands at 229cm, taller than Shaquille O’Neil, who stands at 216cm. However, despite being shorter, Shaq’s wingspan is 8 cm longer than Yao Ming’s.

While there is no reference regarding the ‘speed gene’ and limb length for Asian athletes, we can speculate that it won’t be greater than athletes from other countries. In terms of international success, only one Asian athlete has broken the 10 seconds barrier for the 100m dash since record-keeping began. That sprinter is Su Bingtian from China, with a record of 9.83s in the semifinals of the 100m dash in the 2020 Olympics.

While genetics may be working against Asian sprinters, the equally significant role of lifestyle and environment means there is still a chance for them to gain ground.

Losing a battle but not the war

Though genetic changes happen over many generations, there have been some recorded differences over the short and medium term. For example, Epstein’s data shows that the average height of Asian athletes increased by 1.7 inches (or 4.3cm) from 1957 to 1977. These findings have been associated with improved diet and lifestyle, especially in countries such as China and Japan, which have professionalized their athletics scene.

The results of this have already been seen in track and field, such as when female marathon runner Mizuki Noguchi took home gold in the 2004 Athens Olympics. While there is still ground to make up in the sprinting department, Su Bingtian’s Asian record tops that of Oceania (Patrick Johnson) and South America (Robson de Silva) - only losing to Africa (Ferdinand Omanyala), North America (Usain Bolt), and Europe (Marcell Jacobs).

Furthermore, the role of sports science has been huge in closing the gap. Japan took two decades to break the 10 seconds barrier for the 100m dash after introducing a sports-science-orientated approach to their sprint training. Yoshihide Kiryu finally achieved the feat in 2017, who completed the sprint in 9.98 seconds.

Japan’s R&D team revealed that Professor Akifumi Matsuo, formerly a lead scientist for the National Fitness and Sports Center, was key to their advancements. Their starting point was the form of Carl Lewis, a legendary American track runner who set the world record in the 1991 World Championship which Japan hosted. The researchers analyzed Lewis’s form from the initial kickoff, footwork, body mechanics, and top speed acceleration. Based on their findings, they developed a training regime tailored to their athletes and successfully broke the 10-second barrier.

China and Japan also take scouting talent from a young age very seriously, as they value developing and nurturing those talents to be able to compete at international levels. They not only focus on improving their runners’ technique but also on developing their physical capability to the maximum potential. Although they have not been able to compete against global leaders in their fields, they are indeed getting closer every day.

With these advancements in diets, lifestyle, and sports science, it’s quite possible that today’s generation of young Asian sprinters may finally be able to close the gap and compete with the best in the world.

References:

http://breadbeforerice.blogspot.com/2013/09/why-asians-run-slower.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/100_metres

http://reelfoto.blogspot.com/2012/08/howard-schatz-and-beverly-ornstein.html

https://www.brookings.edu/research/asian-american-success-and-the-pitfalls-of-generalization/

http://nattharapong.blogspot.com/2012/10/blog-post_9317.html

https://www.gotoknow.org/posts/295191

https://nextshark.com/chinese-runner-next-usain-bolt/

https://nextshark.com/abdul-hakim-sani-brown-beats-usain-bolt-mens-200m-finalist/

https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14381253